Number Theory

Recall the equivalence relation if for . This is easily shown to be an equivalence relation:

- Reflexive: has the same remainder as when divided by , hence

- Symmetric: if has the same remainder as when divided by , then has the same remainder as when divided by , hence implies

- Transitive: if has the same remainder as when divided by and has the same remainder as when divided by , then has the same remainder as when divided by , hence and implies

The equivalence relation leads us to if such that . We now denote the remainder of when divided by to be . For example, and . Note that .

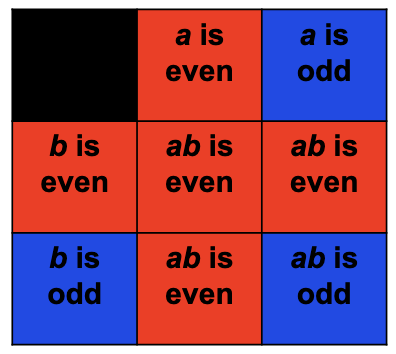

We have that . An example of this is that multiplying two integers and considering the parity (i.e. whether they are odd or even.)

The product of two odd numbers is odd. The product of an even number with another integer is even.

The product of two odd numbers is odd. The product of an even number with another integer is even.

An odd number is equivalent to and an even number is equivalent to . , and . Let and . From the left hand side, we know that such that and and . From the right hand side, .

Clearly, of the four terms in the final statement, three of them are divisible by and hence give no remainder: . Hence the right hand side and left hand side of the initial statement are equal.

But how is this result useful? It can be used to check for errors in large multiplications. For example, imagine you are (incorrectly) told that . At first glance, this seems plausible since an even number multiplied by an even number should be even. Also, we would expect it to end in a 4 and it does.

However, (since and (since ) yet (since ).

Divisibility of 3 and 9

If we write a number in standard base 10 format , for example .

We know that . Since and , we can simply add all of the digits of the number and its equivalence mod will be equal to the equivalence of the number mod . .

TLDR;

Affine Cipher

Considering assigning the integers to the letters . We then define a function . If we choose and such that is a bijection, then this can be used to encrypt a message (such that the message can also be decrypted).

For example, if the simple coding was to , to etc (and to ), then using would map the number (letter ) to , i.e. the 22nd letter of the alphabet, letter V.

How would we decipher a message encoded this way? so . How, though, do we define the multiplicative inverse ?

The multiplicative identity element is , since for all . Just as with “normal” arithmetic, the multiplicative inverse is whichever element multiplies with that element to get to (ie. the multiplicative inverse of multiplication by is multiplication by ).

We therefore define to be whichever number gives .

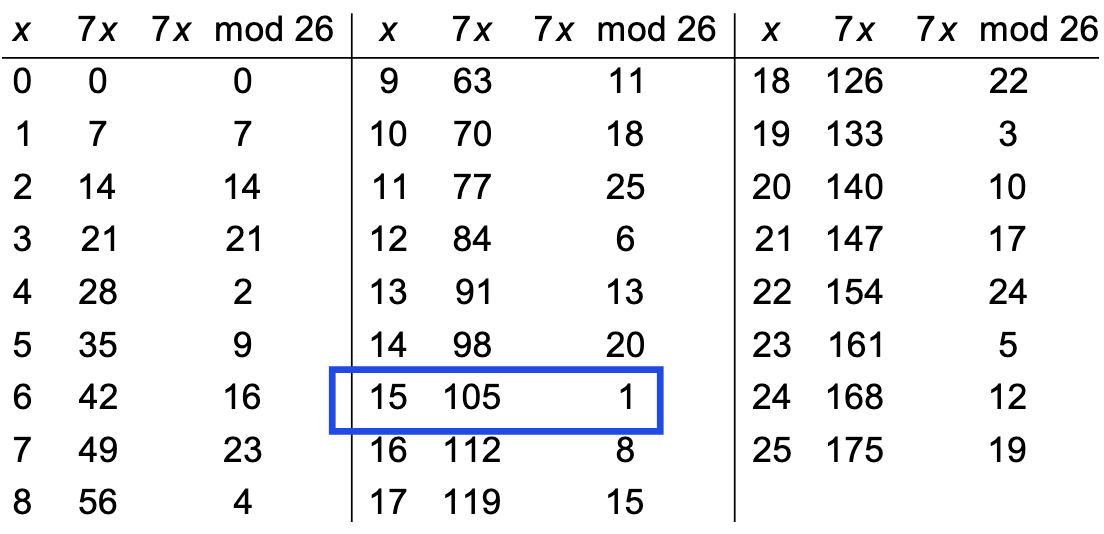

For the multiplier of here is a table of multiplicative inverses.

For example, using would map to .

For example, using would map to .

We can see that multiplication by () is equivalent to “unmultiplying” by (). We would therefore recover the original input of since .

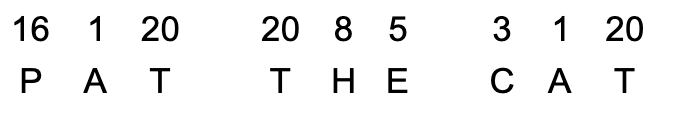

Consider now using and . How would we encrypt the message “PAT THE CAT”?

P would therefore be encoded as D (4) since .

P would therefore be encoded as D (4) since .

PAT THE CAT would encode to DJR RBX DJR. Why is this problematic?

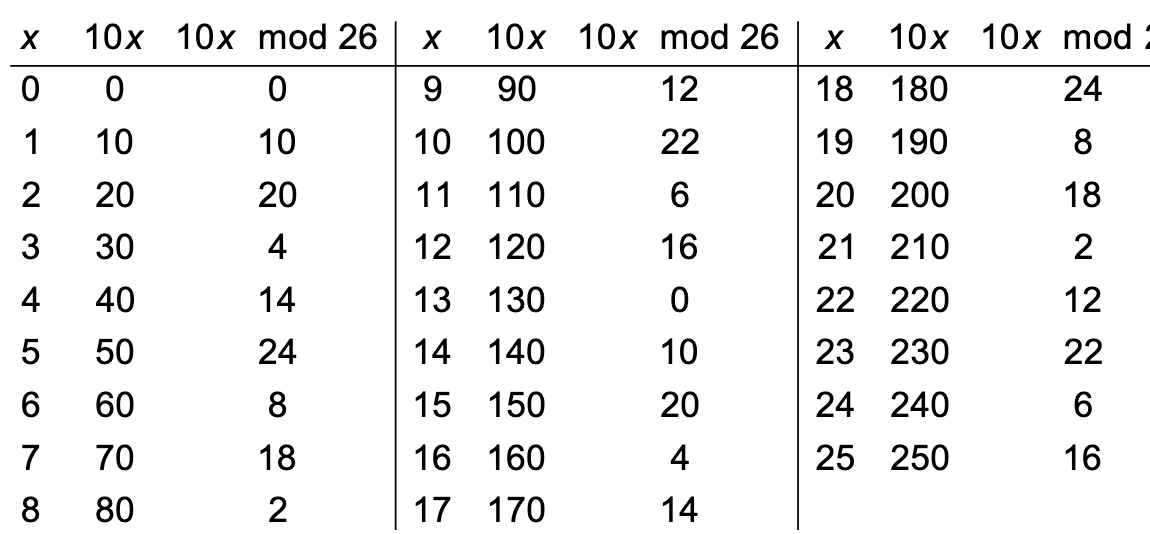

If we look at the equivalent table for a multiplier of , we see there is no element which is equivalent to . No inverse exists.

If we look at the equivalent table for a multiplier of , we see there is no element which is equivalent to . No inverse exists.

TLDR;

Coprimes

We say that two integers and are coprime or relatively prime if . The affine cipher (for a chosen and ) only works if .

When we used , 2 different values mapped to the same output. .

If we chose a multiplier of , each output would be mapped to 13 times (ie. only two possible outputs).

Error Checks

Modular arithmetic is also used to check the validity of credit card numbers. Each credit card number contains a check digit. That is, it can definitely determined from all the other digits. If it does match a given value, the number is flagged as incorrect.

The same system is used for things such as digital recording. Error checks are employed to allow for a slightly scratched CD to play correctly as missing or incorrect information can be inferred from the data that has been correctly read.

American Express credit card numbers are 15 digits long. The first 14 digits contain information about the country in which the card was issued, the issuing bank and the account number.

The error check uses or the Luhn Algorithm. The final number is calculated by adding twice the values of the 1st, 3rd, 5th, …, 13th digits to the sum of all the first 14 digits, multiplying this value by 9 and taking this value modulo 10.

For example, for the 14 digits 3759 876543 2100 be? We calculate .

The 15 digit card number must therefore be 3759 876543 21004. The example number in the American Express image is not a valid number.

Calculations Involving Large Powers

Consider calculating the value of the (absurdly large) number . We can do this by first writing in binary form, i.e. as so in binary form it is .

We can write and hence:

We can then work out each sequential term in this binary expansion: Eventually we reach: This therefore tells us that and that all higher powers of in the binary expansion (ie. 32nd power, 64th power etc.) are also equivalent to .

[3^{1000}]_{34}&=&[3^{512}]_{34}[3^{128}]_{34}[3^{64}]_{34}[3^{32}]_{34}\\ &=&1\times1\times1\times1\times1\times[3^8]_{34} \end{eqnarray}$$ This is a much simpler calculation (which we have already done) $[3^{1000}]_{34}=[3^8]_{34}=33$ # Euler's Phi Function Let $n\in\mathbb{Z}^+$. Define $\phi(n)=|\{x\in\mathbb{Z}^+:(1\leq x<n)\land(gcd(x,n)=1)\}|$. This is Euler's phi ($\phi$) function and counts how many positive integers less than $n$ are coprime with $n$. For example, for $n=10$, $\phi(10)=|\{1,3,7,9\}|=4$. It is easily shown that for any prime $p$, $\phi(p)=|\{1,2,3,\dots,p-1\}|=p-1$ since by definition, a prime is coprime with every integer smaller than it. If $a$ and $b$ are coprime, we have that: $$\phi(a)\phi(b)=\phi(ab)$$ # Euler's Theorem If $a$ and $n$ are coprime positive integers, then $a^{\phi(n)}\equiv1\text{ mod }n$. We prove Euler's Theorem first by defining the set $^*_n=\{x:gcd(x,n)=1\}$. By definition, $|^*_n|=\phi(n)$. We then show that, when taking any element in the set $\mathbb{Z}^*_n$, multiplying it by $a$ and calculating its remainder mod $n$, we simply obtain another member of the set $\mathbb{Z}^*_n$. List the elements of $\mathbb{Z}^*_n$ as $0<a_1<a_2<a_3<\dots<a_{\phi(n)}$. It is easy to show that multiplying an element by $a$ and taking its remainder mod $n$ maps to a unique value since if $[a\times a_i]_n\equiv[a\times a_j]_n$ then $[a\times(a_i-a_j)]_n\equiv0$. As $a$ and $n$ are coprime, then $n$ divides ($a_i-a_j$) but as this value is strictly less than $n$ it must be zero, implying that $a_i=a_j$. The function is therefore one-to-one. We can easily show that it is a bijection, since each of the $\phi(n)$ elements which are coprime with $n$. We complete the proof by considering $$a^{\phi(n)}a_1a_2,\dots,a_{\phi(n)}=(aa_1)(aa_2)\dots(aa_{\phi(n)})\equiv a_1a_2\dots a_{\phi(n)}$$ Multiplying both sides by the inverses $a_1^{-1}a_2^{-1}\dots a_{\phi(n)}^{-1}$ gives $a^{\phi(n)}\equiv1\text{ mod }n$. For example, taking $n=77$ and $a=10$, we know that $\phi(77) = \phi(7)\phi(11)=6\times10=60$. We therefore have that $10^{60}\equiv1\text{ mod }77$. This can be used to calculate multiplicative (modular) inverses quickly and forms the basis of a common cryptography system, **Rivest-Shamir-Adleman** or **RSA cryptography**. ## Some Rules $$\text{if }n\text{ is prime: }\phi(n)=n-1$$ $$\text{if }p\text{ is prime and }a\text{ is positive: }\phi(p^a)=p^a-p^{a-1}$$$$\text{if }a\text{ and }b\text{ are coprime: }\phi(a)\phi(b)=\phi(ab)$$