Countable Sets

A function is a bijection if it is both one-to-one and also onto. That is, is a bijection if every element is mapped to by exactly one element in .

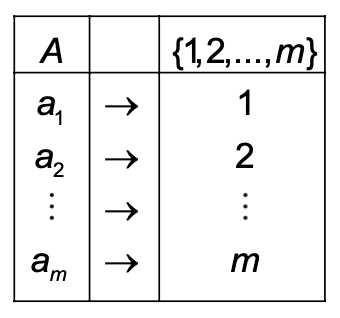

Trivially, every finite set is countable, since if we call the set and its cardinality , we need only select the subset .

For some ordering of the elements of , we then define . The bijection can be visualised with a table showing which elements map to which, showing that this is a bijection and hence is countable:

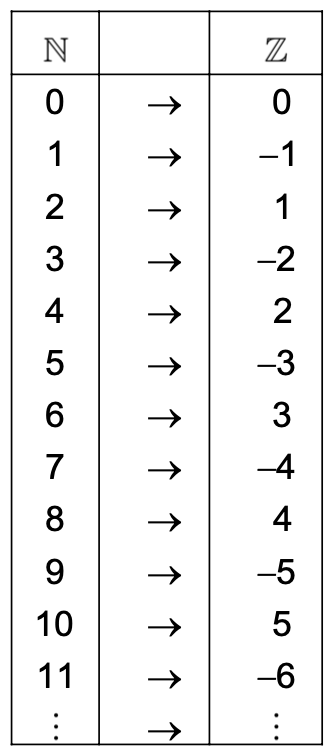

Infinite sets can also be countable. Consider the set , we can define the bijection:

Every element in maps to exactly one element in . We therefore have that the set of integers in infinite but countable. This sometimes referred to as a countably infinite set.

Uncountable Sets

We have already seen that infinite sets can still be countable, however not all infinite sets are. For example, the set of real numbers is uncountable or uncountably infinite. In fact, it can be shown that any finite interval of is uncountable, the most famous proof of this being Cantor’s Diagonalisation Argument.

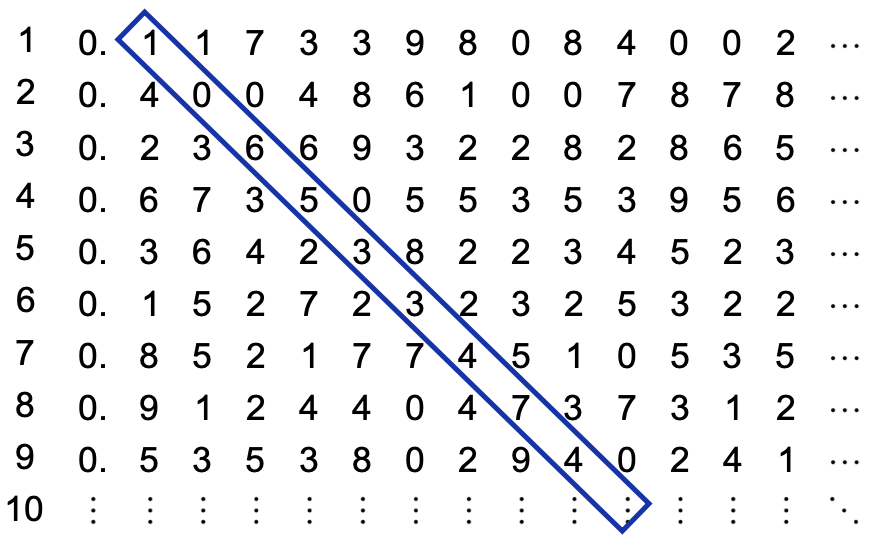

Cantor’s Diagonalisation Argument can be used to show that the interval contains an uncountable number of elements. By contradiction, we first assume that there is a countable list of all real numbers between and . It then demonstrates that, whatever this list contains, there are also additional numbers not in this list, contradicting the assumption that a list of all real numbers in this interval exists.

We can number the rows with natural numbers, so that there exists a bijection between the natural numbers and if all real numbers are in the list.

We can number the rows with natural numbers, so that there exists a bijection between the natural numbers and if all real numbers are in the list.

The argument looks at the digits down one diagonal and forms a new decimal by adding one to each digit. In this example, we produce the number . This value cannot be in the list because each digit must be different. However far down this countable list we go, we cannot find that number. This contradicts that this is the list of all real numbers between and .

Comparing Systems of Algorithms

Consider the following pseudocode:

Define: parameters a (real number), n (positive integer)

Input x

For i=1 to n, replace x:=a * x

Output x

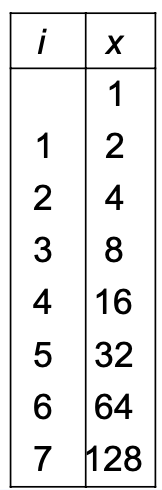

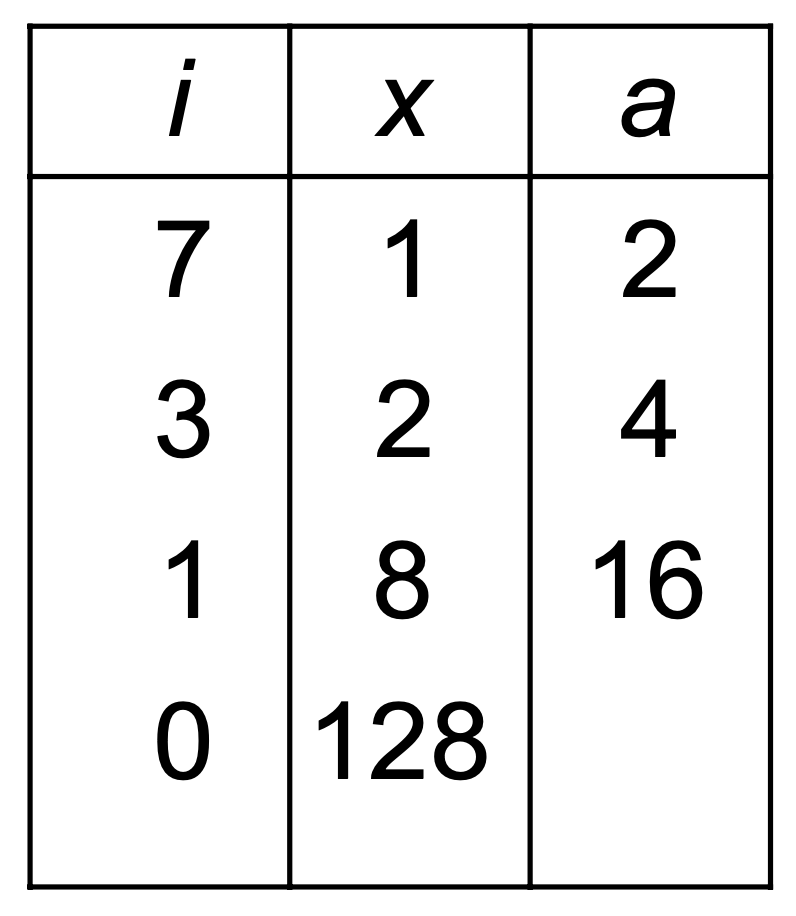

For example, defining would produce the following output for where the output is :

Consider the alternative pseudocode:

Consider the alternative pseudocode:

Define: parameters a (real number), n (positive integer)

Input x

While i>0, if i is odd, replace x:=a * x, replace i:=i/2

If i>0, replace a:=a * a

Output x

For example, defining would produce the following output for where the output is still :

For this example, the second algorithm reaches the output of in fewer steps. This becomes even more apparent if we set a larger power to calculate for some real number . Each increasing power is calculated as additional step, so the first method takes 20 steps.

For this example, the second algorithm reaches the output of in fewer steps. This becomes even more apparent if we set a larger power to calculate for some real number . Each increasing power is calculated as additional step, so the first method takes 20 steps.

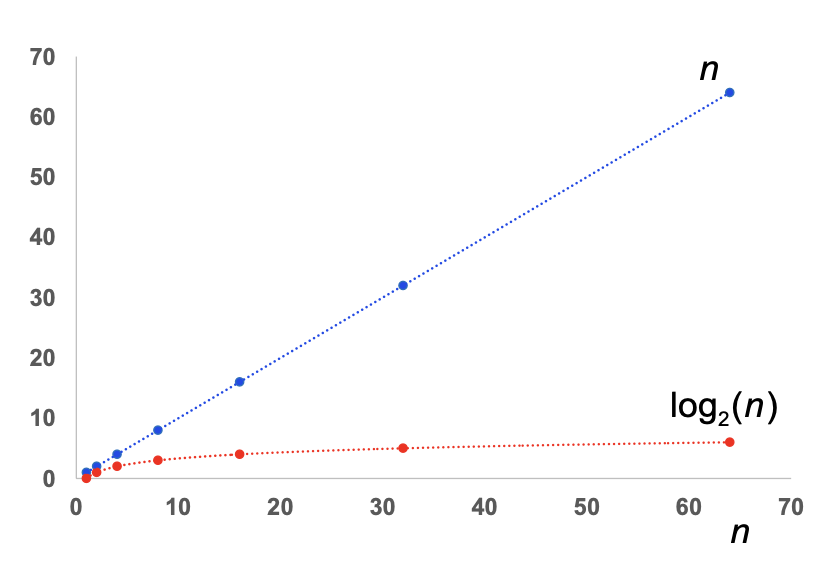

Doubling the in the first algorithm doubles the number of steps case, whereas in the second case it would only add one additional step, since (the remaining power) halves with each step. The number of steps taken in the second algorithm therefore scales with increasing proportionally to :

We compare the speed or complexity of an algorithm by considering how the time or steps taken by the algorithm changes as the input value of changes. This is usually done by comparison to a simpler function, for example earlier, the number of for one steps for one increased approximately proportionally to whereas the other increased proportionally to .

We compare the speed or complexity of an algorithm by considering how the time or steps taken by the algorithm changes as the input value of changes. This is usually done by comparison to a simpler function, for example earlier, the number of for one steps for one increased approximately proportionally to whereas the other increased proportionally to .

Dominance

Let and be functions . We say that dominates if there exists constants such that for all . This can be written as or said as ” is in Big O of ”. is the set of all functions between the natural numbers and real numbers which are dominated by .

We could see graphically that the function dominated . We want to be able to prove such statements analytically. For example, we can prove that dominates .

Clearly for . We then need to show, for a proof by induction, that if true for , then it is also true for .

Assume for some . We then have that . Similarly . Since , we have that . Since is a natural number, this gives . Setting in our definition for all completes the proof that dominates . .

A Couple of Notes on Complexity and Speed

For some small input values , an algorithm which is “slower” might actually run in fewer steps. For example with and , a small will result in being quicker.

In general however, we are more concerned about scalability. Also, for inputs that are small, the difference in speed is usually trivial.

Also, although we tend to use when discussing complexity, an algorithm which scales logarithmically with the input value does so whatever the base of the logarithm. This is because . and are just constants.

Pigeonhole Principle

The axiom of the pigeonhole principle says that if pigeons occupy pigeonholes and , then at least one pigeonhole has multiple pigeons in it.

For example, if you have a group of 8 people, there is at least one day of the week on which more than one of the group was born. Here, the 8 people are “pigeons” and the 7 days of the week are “pigeonholes”.

We can apply the pigeonhole principle to prove that any time we select 5 integers from the set , we will always select two numbers which sum to . There are four pairs of numbers which sum to (, , , ). We can then define the 5 numbers we select as the 5 pigeons and the 4 possible pairs summing to 9 as the pigeonholes.

Another example

Consider the example of a group people. We can prove that at least two of these people have an equal number of friends in the group (assuming that friendships are symmetrical, ie. Person A is friends with B so B must be friends with A).

Assuming everyone has at least one friend, then each person has between and friends in the group. Defining the people as pigeons and the set of people with 1 friend, the set of peple with friends, …, the set of people with friends as the pigeonholes, we have that at least two people have the same number of friends.

If there exists one person with no friends, then we have people each of whom have between and friends and hence the same pigeonhole principle argument holds.

If there exists two people with no friends, then the statement is obviously true.