Graph Theory

A graph is a pair of sets and such that each element is associated with some subset containing either 1 or 2 distinct elements. The elements in are vertices or nodes, and those in are edges.

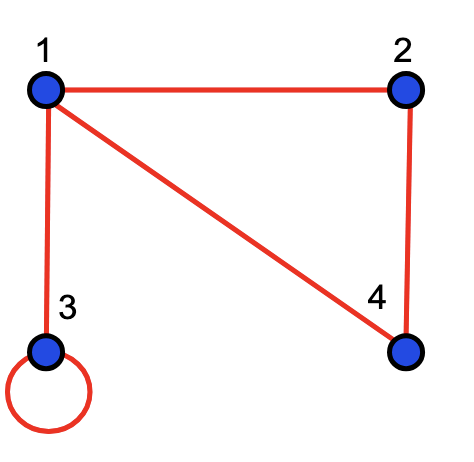

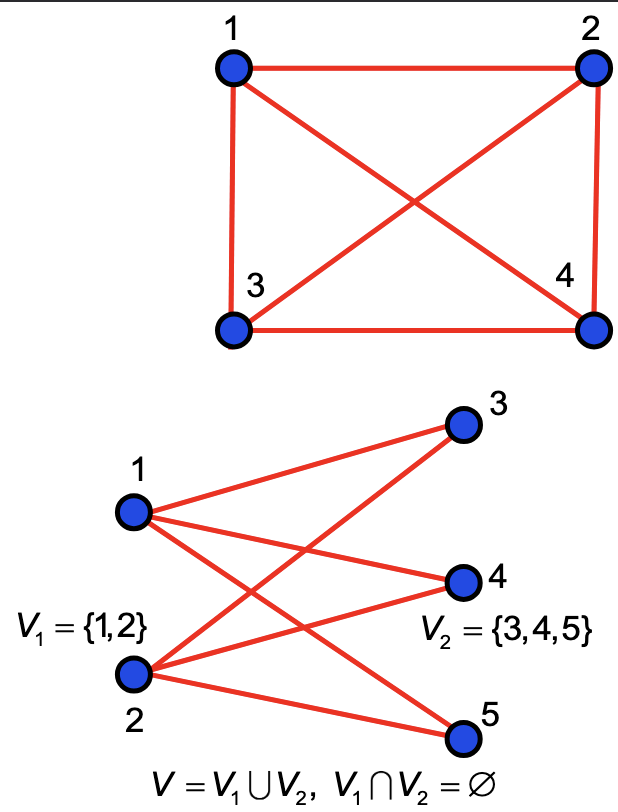

Consider the example and where represents the edge associated with . We visualise this with four dots, labelled for the vertices and five lines joining these representing the edges.

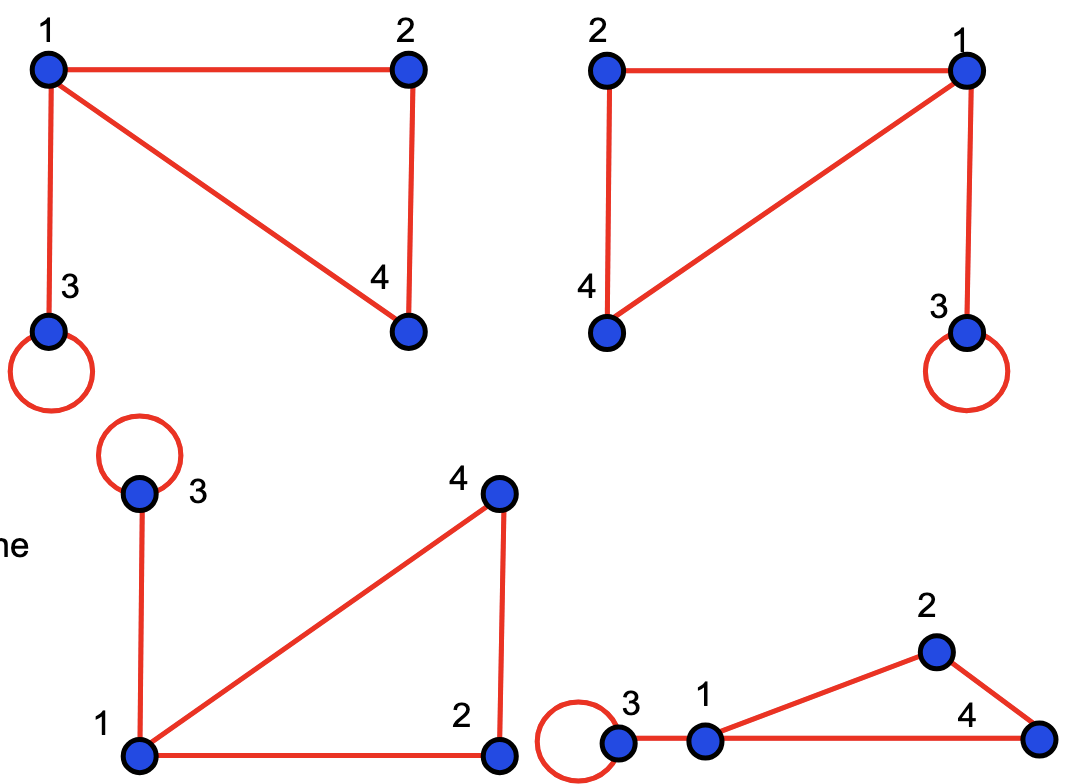

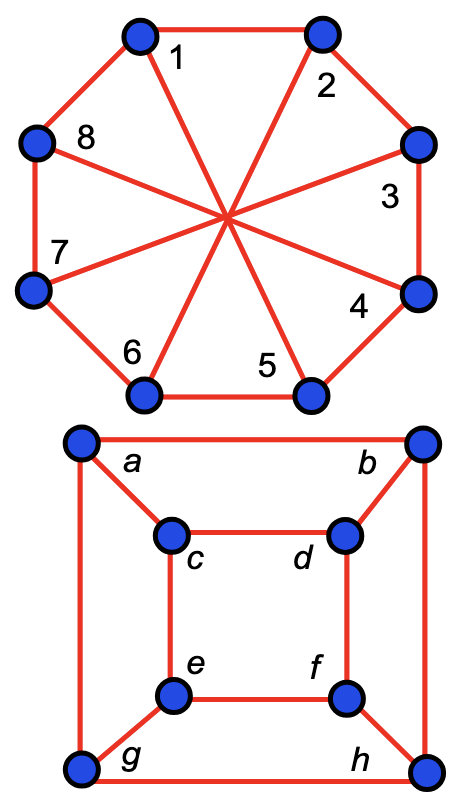

Note that the exact same graph can be visualised in many different ways, including but not limited to rotational or reflective symmetry. For example, each of the following four graphs are the same. Each is a representation of the same and .

Definitions

If the subset is associated with more than one edge in then is a multigraph and these multiple edges are multiedges.

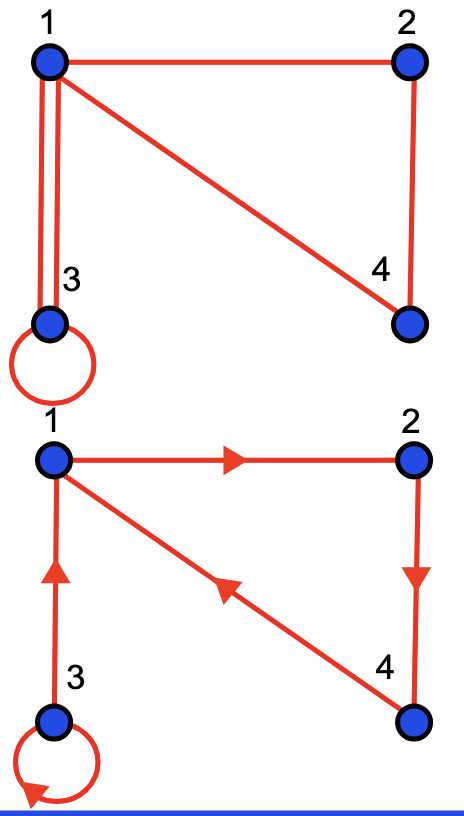

A directed graph is one such that each edge is associated with an ordered pair . The first element in the pair is the source node (or vertex). The second element in the pair is the terminal node (or vertex). In a directed graphs, edges will have arrows.

A loop is an edge from a node to itself. In an undirected graph, this is a subset of with one element. In a directed graph, it is an ordered pair with the same source and terminal node.

A loop is an edge from a node to itself. In an undirected graph, this is a subset of with one element. In a directed graph, it is an ordered pair with the same source and terminal node.

A simple graph is one with no multiedges and no loops.

A path is a sequence of edges such that for all , . In other words, a path is a sequence of edges such that each edge shares one node with the previous edge.

A path is a simple path is all nodes are also distinct i.e. if for all .

A circuit or closed path is one such that the first and last edge of the path share a common node.

The length of a path is simply the number of edges in the path.

A graph is connected if, for every pair of nodes , there exists a path starting at and ending at .

An edge is incident to a node if that node is contained within the edge.

Two nodes are adjacent if there is an edge which contains both of them.

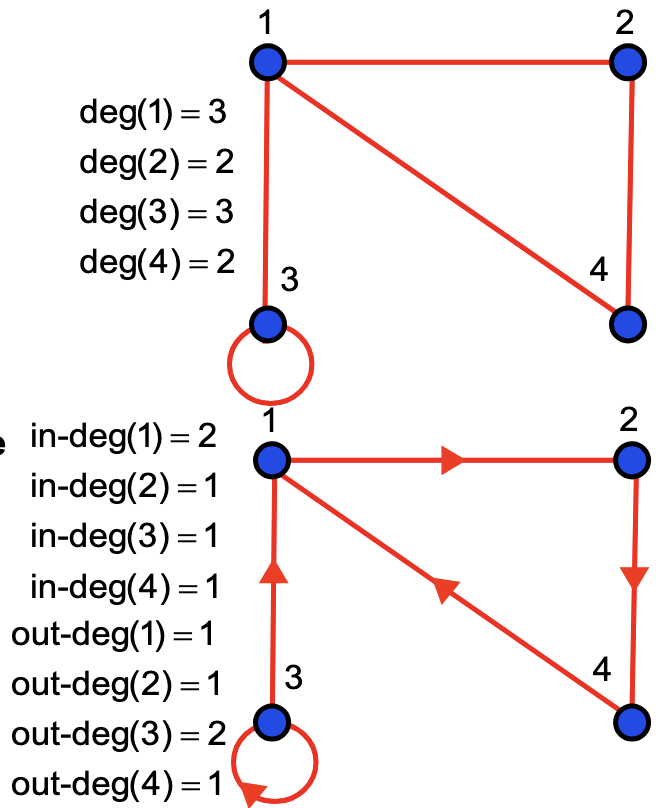

In an undirected graph, the degree of a node (usually written as ) is equal to its number of adjacent vertices, counting any loops twice.

In a directed graph, each node has an in-degree and an out-degree, counting the number of edges going into and out of the node respectively.

A complete graph on nodes is one which contains all possible distinct edges. That is, if then .

A complete bipartite graph is one whose nodes can be partitioned into two subsets such that every node in the first subset is adjacent to every node in the second subset.

Let be a graph (either directed or undirected) with . The adjacency matrix for is an matrix such that is the number of edges from node to node . As with the degree of a node, typically loops are counted twice for an undirected graph.

Proof of Sum of Degrees of Nodes

We can now prove that, for an undirected graph where , the sum of the degree of each node .

Trivially, this is true if since a graph with no edges has all nodes with no edges hence all nodes have degree zero. If we assume it is true for , consider adding one more edge to the graph. The new edge either connects to two nodes, thus increasing both of their degrees by one, or else it forms a loop connecting one node to itself, thus increasing its degree by 2.

By induction, we have that it is true for and by the above argument, therefore true for all positive integers .

Proof of Path Lengths

Let be a graph with adjacency matrix . We can now prove that the number of paths of length starting a node and ending at node is given by the -th element in the matrix .

By definition of the adjacency matrix, this is true for n=1 since the -th element in the matrix is set as the number of edges from node to node , which is equal to the number of length 1 paths between and .

We can now use induction to prove that the statement is true for all positive integers .

Assume that it is true for some . This tells us that the number of paths of length betwee node and node is where .

. By the definition of matrix multiplication, we multiply by summing the pairwise products of elements along the rows of with those down the columns of . The -th element in is therefore .

This sums the number of paths whose first step is from to (for some ) and which subsequently takes an additional steps to get from to .

Graph Isomorphisms

Let and be graphs (not multigraphs).

We say that and are isomorphic if there exists a bijection such that for all we have if and only if .

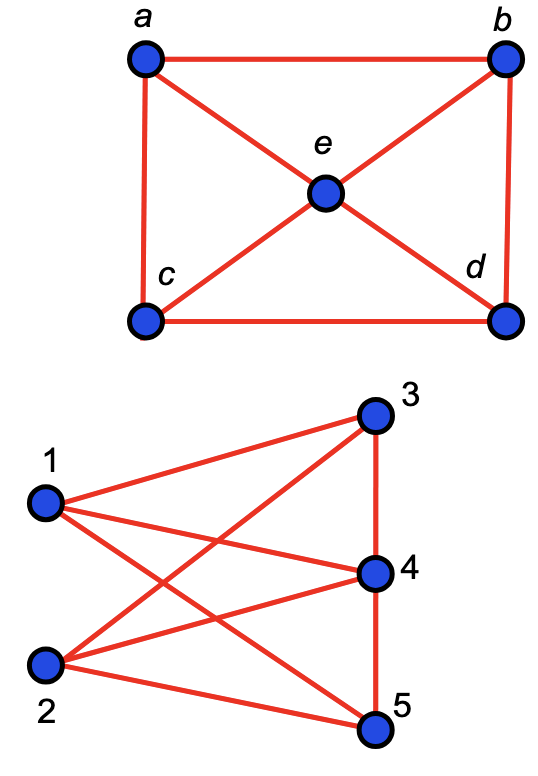

Here, we have , , , and .

Invariants

A statement is invariant for the graph isomorphism if and only if, for isomorphic graphs and is true for the graph if and only if it is true for the graph .

Examples of graph invariants include:

- The graph has nodes

- The graph has edges

- The graph is connected

- The graph has nodes of degree

- The graph has circuits of length

Note that finding that two graphs share one or more of these properties does not prove that they are isomorphic, however showing one of these statements holds for one graph and not the other is sufficient to show that they are not isomorphic.

For example, we can show that the above two graphs cannot be isomorphic. Both graphs contain nodes and edges, however this does not prove that the graphs are isomorphic. In fact, the first graph contains circuits of length (for example but the second graph contains no circuits of length ). They are therefore not isomorphic.

For example, we can show that the above two graphs cannot be isomorphic. Both graphs contain nodes and edges, however this does not prove that the graphs are isomorphic. In fact, the first graph contains circuits of length (for example but the second graph contains no circuits of length ). They are therefore not isomorphic.

Euler Paths and Circuits

An Euler path in a graph is one which uses every edge exactly once.

An Euler circuit is an Euler path which is also a circuit.

It is easy to prove whether or not a graph contains an Euler path or circuit. If any node has odd degree, then it is impossible to use every edge of the graph without getting stuck.

If every node has (non-zero) even degree, then it contains an Euler circuit. A graph can still contain an Euler path if it has either zero or two nodes of odd degree.

In the latter case of two nodes of odd degree, these will be at the start and the end of the path.

Königsberg Bridge Problem

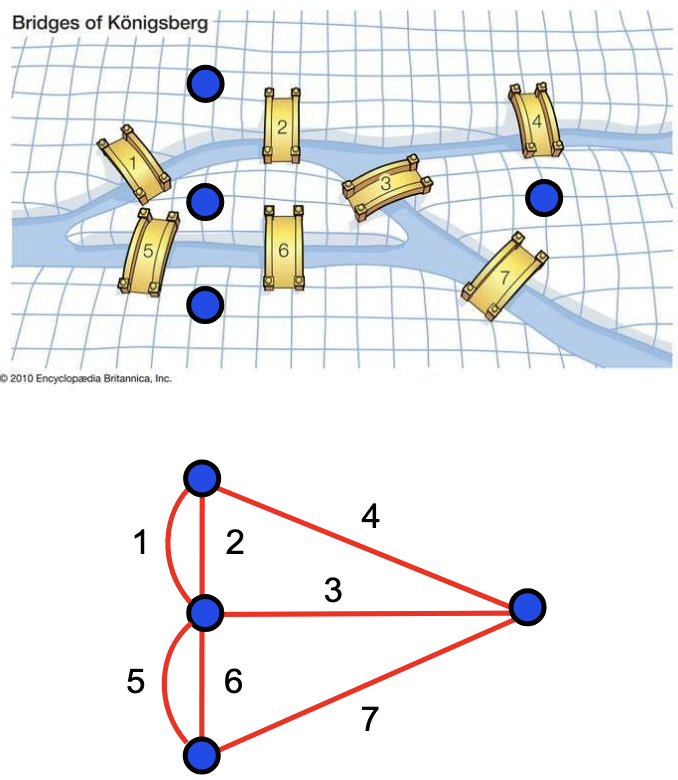

The most famous problem involving Euler paths is the Königsberg Bridge Problem.

The city of Königsberg had seven bridges spanning its river network. The problem was posed for a traveller to cross all seven bridges without crossing any twice. This is equivalent to finding a Euler path on the resultant graph.

No such path exists, as proved by Leonard Euler.

Hamiltonian Paths and Circuits

There is a similar definition to Euler paths and circuits, defined by the presence of nodes, rather than edges. A Hamiltonian path in a graph is one which uses every node exactly once. A Hamiltonian circuit is one which starts and ends at the same node. A number of similar theories exist for the study of Hamiltonian paths and circuits, but are not covered in this subject.