Counting Arguments

Consider a race with 8 runners such that the runner finishing first/second/third are given gold/silver/bronze medals. How many different ways could the three medals be allocated? There are 8 runners who could win gold. Once this is fixed, there are 7 remaining ones who can win silver, and 6 respective remaining runners for bronze. We therefore have potential outcomes for assigning the three medals. Mathematically, this is saying that there are 336 possible one-to-one functions mapping the set of 3 medals to the set of 8 runners.

So here, there are 336 possible one-to-one functions for and .

In general, for , we have one-to-one functions . This is equal to possible one-to-one functions. Note that if , then the pigeonhole principle tells us that we have no such function (there are three medals but less than three runners).

Multiplication Rule

Consider a Mr Potato Head toy which has:

- 3 possible sets of feet

- 2 possible noses

- 3 possible hats

- 2 possible mouths

- 2 possible pairs of eyes

- 2 possible pairs of ears

- 5 possible accessories Assuming exactly one of each category is required, how many configurations of the toy are there? .

Addition Rule

Consider a case where instead of picking one item from one set and one item from another, we need to pick one item either set or set , but not both. For simplicity, initially assume that the two sets are disjoint, that is that every element in is not in and vice versa. We then have ways to pick an element from and ways to pick an element from . This therefore gives us ways to pick one element from either or . This, however assumes that and are disjoint.

Non-disjoint sets

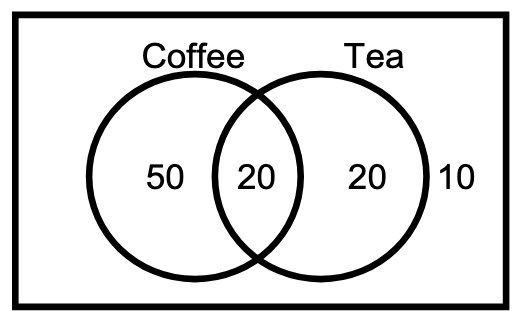

Consider a survey of people’s hot drink consumption. 70 respondents said they had drunk coffee the previous day, 40 respondents said they had drunk tea the previous days. How many people had drunk either tea or coffee (or both) the previous day? The number could be as many as 110 (if everybody drank only one type of drink) or as few as 70 (if all coffee drinkers also drank tea).

To answer this question, we would also need to know the number of respondents in both the set of coffee drinkers and also in the set of tea drinkers.

Suppose we know that 20 people drank both types of drink, and that a total of 100 people responded. Here, the simple count of 70 coffee drinkers plus 40 drinkers “double counts” the 20 people who are in both sets. The total number in at least one set is therefore .

Inclusion-Exclusion Principle

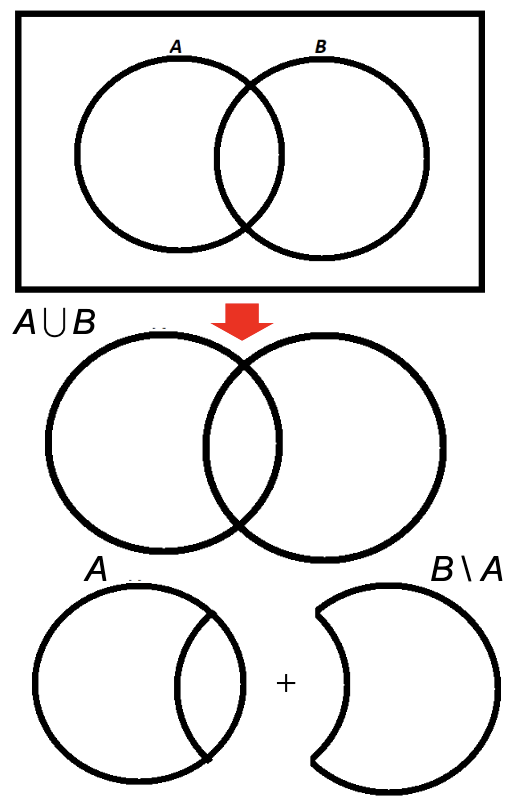

Let and be sets which may or may not be disjoint. The number of element in either or (or both) is equal to the sum of the number of elements in and the number of elements in minus the number in both.

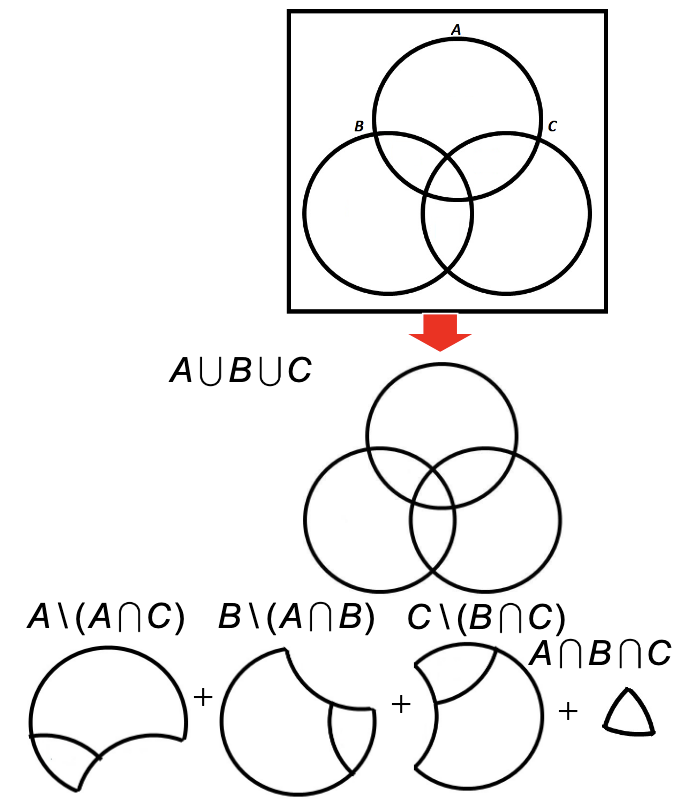

This can be justified (but not proven) graphically. And can be extended to more than one set, for example

And can be extended to more than one set, for example  Similarly, the principle extends to any number of sets, for example with four sets:

Similarly, the principle extends to any number of sets, for example with four sets:

Permutations

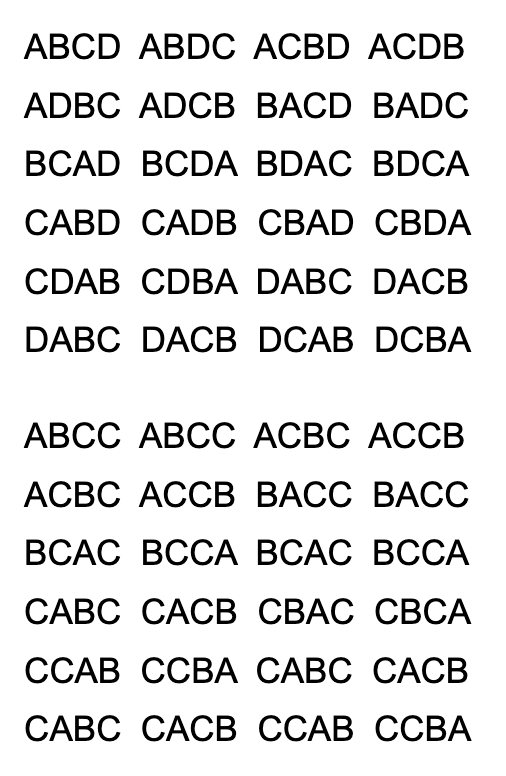

Consider the number of ways that the four letters , , and can be arranged. We have already seen t hat we would have four choices for the first letter, then three remaining choices for the second, two remaining for the third and one remaining for the fourth, which gives permutations ().

Doing 4 letters for three spots would be .

Permutations with Repetition

Consider the number of ways that the four letters , , and can be arranged. Note that the letter appears twice.

For example, compared to the old list of 24 elements, each string now appears twice, leaving only 12 permutations with the repeated character.

Where a character appears times, there are repetitions associated with that character’s appearance.

Where a character appears times, there are repetitions associated with that character’s appearance.

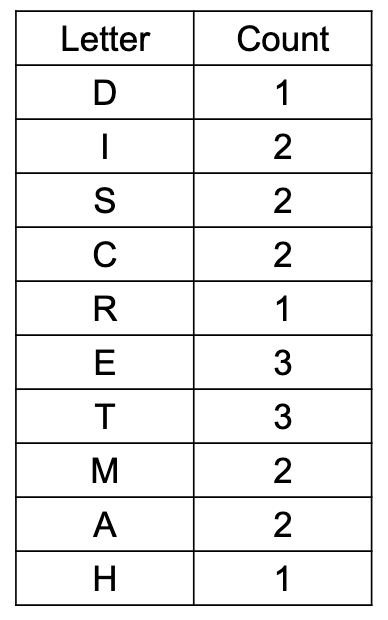

Consider the number of ways that the 19 letters can be arranged. There are clearly ways, not accounting for repeated letters. To account for this, we divide the total permutations by the repeated permutations of each letter:

Combinations

Consider travelling around Melbourne’s grid system. The entrance to Etihad Stadium is located six blocks west and two blocks north of Flinders Street Station.

Assuming you never walk backwards (i.e. south or east) how many different routes are there for the journey (sticking to the main grid system and not using any laneways or smaller streets)?

You must walk 8 blocks in total, 6 west and 2 north. This problem therefore reduces to find the number of arrangements of .

There are therefore .

This problem can be considered as one of simply picking which two of the eight positions we choose to walk north. When selecting elements from a set containing elements, we have: This is often said as ” choose ”.

Binomial Theorem

Consider repeatedly flipping a (possibly biased) coin which lands Heads with probability and lands Tails with probability on each flip. What is the probability that 3 Heads are obtained in 10 flips? The probability of (in order) is . This though is only the probability in order of .

We have already seen that there are outcomes which consists of 3 Heads and 7 Tails.

The probability of 3 Heads is therefore . This result generalises to Heads in flips occurring with probability: If we add up the possibilities of all possible outcomes of flips (from obtaining 0 Heads, 1 Heads, …, n Heads), we must have a probability of 1:

This gives us the binomial theorem, which tells us that:

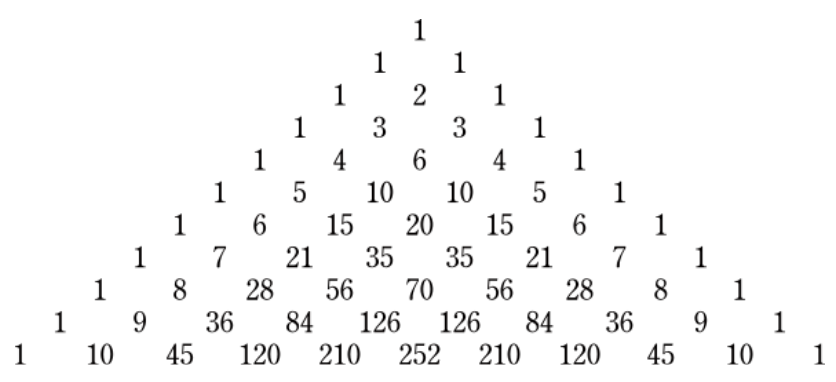

This is commonly seen in many branches of mathematics, including pascal’s triangle.

The entry on the .