Ordered Pairs and Cartesian Products

An ordered pair is best thought of as a tuple where the order matters as opposed to sets which are unordered (where is identical). The cartesian product of sets and is defined as . is the set of all ordered pairs of all elements in and .

For example, for the sets of vehicles and colours , the cartesian product is:

\begin{eqnarray} C\times V =&& \{(\text{red},\text{car}),(\text{white},\text{car}),(\text{black},\text{car}), \\ && (\text{red},\text{van}),(\text{white},\text{van}),(\text{black},\text{van})\} \end{eqnarray}Relations

We call the subset a relation from to .

For example, consider and with relation . In this case, the relation can be written as (all of ‘s elements are in set , all of ‘s elements are in set , and all of the elements in divides ). We can write , or ” is related to ” if , for example , ,…,.

Some properties of relations include: let be a set

- is reflexive if for all

- is symmetric if for all

- is antisymmetric if for all

- is transitive if for all

Example A

Let and .

- is not reflexive ( is missing)

- is symmetric (every pair also appears with the order reversed)

- is not antisymmetric ( and exist in the set but )

- is not transitive ( and exist in the set but is missing)

Example B

Let and .

- is reflexive (every positive integer is divisible by itself)

- is not symmetric ( but )

- is antisymmetric (the only integer where a divisor and a multiple of a given integer is itself)

- is transitive ()

Equivalence Relations and Partial Orders

| Properties | Equivalence Relation | Partial Order |

|---|---|---|

| Reflexive | ✅ | ✅ |

| Symmetric | ✅ | ❌ |

| Antisymmetric | ❌ | ✅ |

| Transitive | ✅ | ✅ |

Equivalence Relation Example

A relation that is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive is an equivalence relation. For example, we can show that is an equivalence relation from any non-zero integer .

Recall that for integers and , .

- For any integer , divides since zero is divisible by all non-zero integers. This implies that the relation is reflexive.

- If , then such that . Rearranging gives us , hence such that (where ). This implies the relation is symmetric.

- If and , such that and . This gives , implying the relation is transitive. These three confirm that the relation is an equivalence relation.

Partial Orders

A relation that is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive is a partial order. For example, we can show that is a partial order on the set of integers.

- For any integer , . This implies that the relation is reflexive.

- Similarly, for any integers and , and if and only if . This implies the relation is antisymmetric.

- For any integers , , and , if and , then . This implies the relation is transitive. These three confirm that the relation is a partial order.

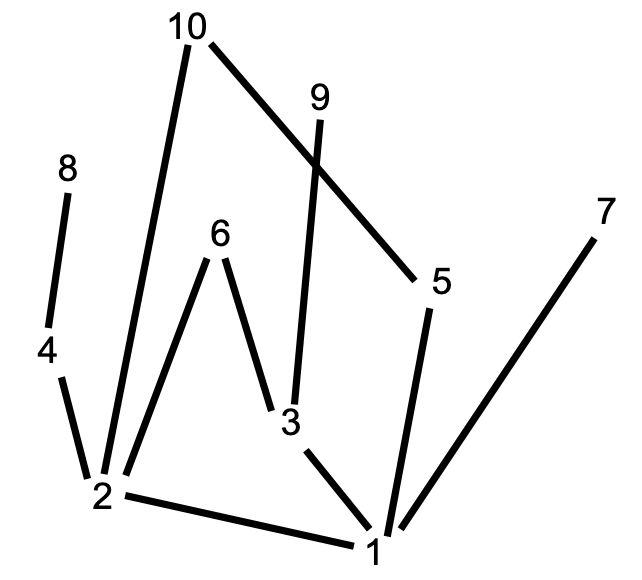

Hasse Diagrams

One way to visualise a partial ordering is a Hasse diagram. It is effectively a directed graph with the elements as nodes and directed edges denoting the relation. The graph is simplified by:

- Not including edges from an element to itself (does not show reflexivity)

- Not including transitive edges. These can be inferred

- Not explicitly including directions on the edges, rather placing that all arrows are directed upwards.

Consider the set and the relationship . We want to visualise , as well as dividing into every prime number (since every other number can be inferred transitively).

Functions

A function is a relation where every element of appears exactly once as the first component of the ordered pair. For each , we have exactly one . We often use the notation and can write .

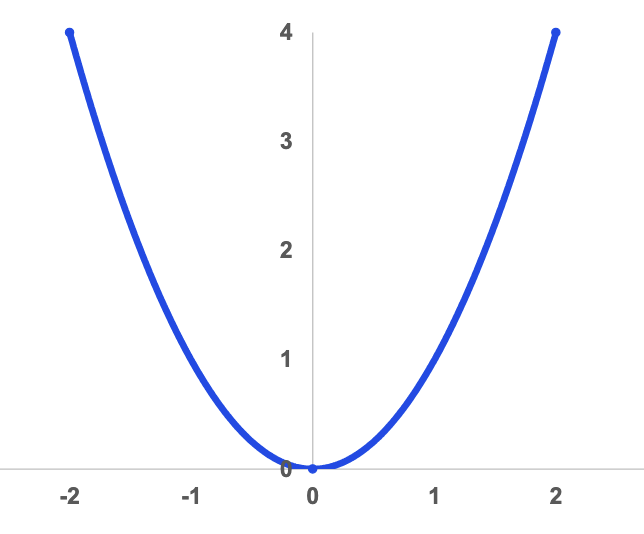

Consider the sets and with the relation . In other words, for every element in , the corresponding element in in the ordered pair is the square of the value of . Points in this relation include etc.

One-to-One Functions

For sets and , a function is one-to-one if . Informally, this means that if the second component of two ordered pairs are the same (the outputs), the corresponding first components must be the same (the inputs). Graphically, this is obvious when it fails the horizontal line test, like the previous example.

This is also verified algebraically, since but .

This is also verified algebraically, since but .

Consider the linear function, for . Graphically, this can be easily seen, however it can be also be proven algebraically:

Onto Functions and Bijections

For sets and , a function is “onto” if such that .

It is easy to show that for any linear function is onto, provided is non-zero. We simply need to show that, for any such that . We can prove this directly by setting so that .

A function which is both one-to-one and onto is a bijection.